Since July, I’ve been working with a private client whom I see twice a week for 2-hour sessions at the nursing home where she lives. Anna (a pseudonym to protect her privacy) is an impish-looking woman who used to work in human services, and still retains a life-long love of folk music and the great outdoors. Her hiking legs aren’t what they used to be but she still gets around without a cane or walker, climbs steps on her own by grasping onto the railing, and opens doors by herself. She is where she is because of a dementia diagnosis and physical ailments that require nursing oversight. Despite two hearing aids, it’s hard for her to understand anyone who’s not addressing her directly.

She usually waits for me at the front entrance, impeccably groomed in a knitted polo, crew neck sweatshirt, spotless jeans, and fashionable walking shoes, and with a tale of woe that varies only in the order of its sentences from one visit to the next: “I can’t take it anymore. I’m depressed and miserable. I’m bored out of my mind and have no friends. This is no way to live. I’ve got to get out of here.” Sometimes, there’s so much desperation in her voice and body language that my heart goes out to her — I want to wave a magic wand that will immediately whisk her to some eldercare nirvana. Unfortunately though, there’s no such thing in the ElderSparks toolkit. Nor do I know of a better place she can realistically go.

I was hired to supplement the facility’s programming, and bring more stimulation into Anna’s life, by two of her younger friends who are now responsible for her well-being. The psychologist she sees thought we’d be a good match, and the last few months have proven her prescient. Right from the start, we’ve had a warm and engaging relationship with lots of highs. At first, we explored different forms of artistic self expression: drawing, which turned out to be more of a kinesthetic experience; improvisational vocal and percussive sound making; folk singing; movement “conversations”; poetry (we both like Mary Oliver); sunprints; and more.

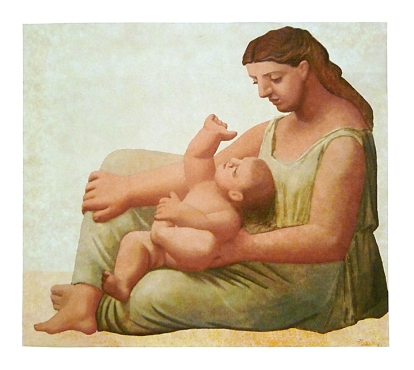

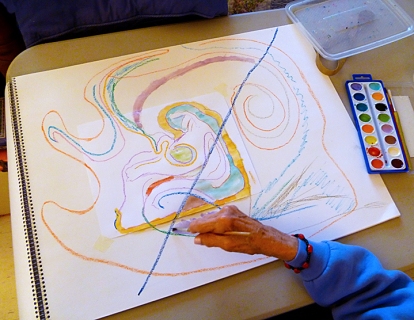

In one of our earliest sessions, I had Anna trace the outlines of Picasso’s Mother and Child (top photo with background removed ), and then fill in the lines (bottom photo). Her drawing was very free and expansive, with strokes extending well beyond the original page. Where I saw an umbilical cord flowing out into the universe, she saw the movement of her arm and hand across the paper. She said that the strong diagonal line was “disturbing but intentional,” and later admitted it was probably a mistake.

This is a pastel drawing Anna made while listening to my repeated readings of Mary Oliver’s poem, The Fish. Gradually I dispensed with all feeling and recited the words as if from a list. At times, she drew with her eyes closed as she swept her arm across the page in a kind of trance/dance. Between the two of us, it felt like we were in an avant-garde theatre piece. Anna explained afterwards that the words and their meaning disappeared at a certain point leaving only sound and rhythm behind.

[space]

Lately, we’ve been spending most of our time in conversation — something she doesn’t have, except in a superficial way, with other residents whose dementia is more advanced than hers. Because of her interest in people, we talk a lot about relationships and psychological development. Once in a while, I’ll share some issues of my own, primarily to distract her from the emotional pain she’s in, but also for my benefit. She’s a very good listener whose perspective is always helpful. I could easily fool myself into thinking she was my therapist :)

A few weeks ago, I wanted her to look again at the poem by Mary Oliver entitled Wild Geese. Given her admiration for Oliver and love of nature, I thought that the last five lines might be particularly comforting to her whenever she got stuck in aloneness:

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting —

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

Her reaction came as a surprise to me: she hated the ending and thought the poem was better without it. When I asked why, she explained that people have to come to their own realizations on their own and in their own time — it’s useless to suggest something outside of the reality an individual lives in, imagined or otherwise. I had to admit it was a valid point but more significantly, I saw that this was how she was asking me to relate to her.

As we’ve delved into her past together, some powerful breakthroughs and insights have occurred. The only daughter of an agoraphobic mother, and father who rarely spoke to Anna, she always wanted her parents to be like normal people. At 13, realizing they weren’t going to change, she decided she needed to distance herself as best she could. Fast forward 70+ years, and here she is reliving her childhood nightmare: surrounded again by people who aren’t available for conversation or ever going to be the adults she so desperately craves for company. As far as she’s concerned, there’s no way out but to leave — except she can’t for reasons her cognitive impairment won’t allow her to acknowledge.

At times, I’ve felt like the asylum doctor in the Argentinian film Man Facing Southeast who can’t decide if his new patient is telling the truth when he claims to be visiting from another planet, or mentally unstable like the others. (Unlike the mysterious patient who quickly becomes a teacher and advocate for his fellow inmates, Anna stubbornly resists sharing her talents with the facility’s residents.) She and I have discussed the possibility of turning her private room into a sanctuary — a base to return to from outings her caregivers regularly take her on — where she can read, write, and do art. (In two months, she has yet to finish the Mother & Child drawing she began, or make use of the art materials and small keyboard I have left on a worktable in her room.) Initially, she used depression as an excuse for her lack of motivation, but more recently, she revealed that she has never been able to nurture herself: she’s always had to have friends around to entertain her. “The only way I know I’m alive is that I have friends,” she says.

It’s frustrating to see this intelligent, passionate, gifted, fiercely independent woman who still has much to contribute unable to adapt to her new reality — and unwilling to even try. Whether it’s a function of her personal proclivities, her self-image as an outsider, dementia, or a combination of all three is hard to say. Life seems to be presenting her with an opportunity to transcend some primal long-term patterns that no longer serve her, but at this stage, perhaps the lesson comes too late. How does one build on new self-knowledge if the discovery is forgotten hours later?

To be continued, that’s for sure.

Amazing stuff, isn’t it? So sorry your efforts were shut down. I hope there have been others since.

Thanks Lynn. Fortunately, there have been other opportunities.